04 Oct Life is more than A grades

4 October 2011, by Phillip Hodson

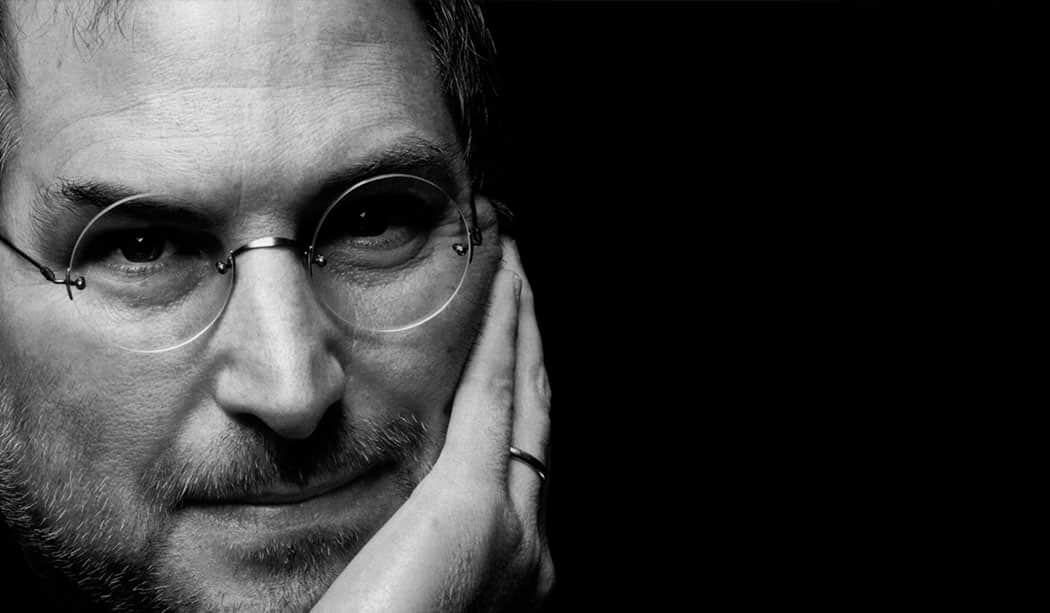

Winston Churchill, Steve Jobs, Henry Ford, Alan McGee and Mark Zuckerberg all either dropped out or didn’t attend university. So, asks Phillip Hodson, why the obsession with grades and educational performance?

You cannot open a newspaper now without reading dire warnings of the plummeting value of every type of educational qualification from English tests at Key Stage 3 to the majority of university degrees.

Not only will you read that pupils are not as clever as they used to be, but also that the volume of students has so flooded the market that graduate wages have fallen. One in five people who left college last year has attracted absolutely no wages at all, and remains unemployed. So even if your child does well in exams, what the hell does it count for?

Well, I agree that standards are not what they were. When I did A level history, for instance, you could be docked five marks for every spelling mistake. If that was done today it would probably result in students, if they ever bothered with history, achieving a minus score.

We also had to praise the career of Britain’s previously most corrupt Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole, in mind-numbing detail after spending three hours in the morning doing a maths exam without benefit of calculators. But to what point? We ended up as parrots with long memories, able to toss off a three-hour essay on any subject we’d mugged up on the night before yet pernickety to the point of insanity about the spelling of ‘venal’ and ‘nepotistic bastard’.

Oh yes, standards then were higher – and so was the price. I worked like a devil for my A grades but didn’t go out for 24 months because I was too busy reciting irregular verbs at bedtime instead of kissing my girlfriend.

So I wouldn’t worry too much about the slurs. We share the same future. Your child must be educated to deal with a world of team meetings, not spelling tests; to display lateral thinking, not tunnel vision. The fact remains that most foreign students still believe British A levels and degrees are worth having. The market, at least, insists they represent good value.

But if your child is seeking a job, not a vocation, then university may no longer be the wisest choice. The value of a degree in the earnings’ table is falling by about one per cent each year. Employers, while disillusioned with graduate immaturity, are willing to recognise that some potential high-flyers may decide not to apply to college because they are worried about debt.

So leaving school at 16 is no crime against self-interest. Those who go straight from school into work enjoy an earlier income for longer. In terms of mere pounds and pence, over a working lifetime, they miss out by less than you might assume. A thick slice of each year’s graduate crop ends up accepting menial work.

And contemplate this irony: one of my son’s friends found himself being interviewed for a banking job by the degree-less boy he used to help in the fifth form maths tests.

Just as well, really.

No Comments